Latest online article in the Ecologist about Mike Roselle, Climate Ground Zero’s Director. The piece is about the state of mountain top removal coal mining, the politics of West Virginia’s coal apologists, and just why Roselle delivered blasting dust debris to Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin’s mansion in Charleston on Thanksgiving last year. Then, just a few weeks later, Freedom Industries rusty, leaking chemical tank of MCHM leached into the Elk River, contaminating the downriver water supply of 300,000 residents of Charleston, after being “filtered” by American Water’s treatment plant.

Courtesy of www.theecologist.org

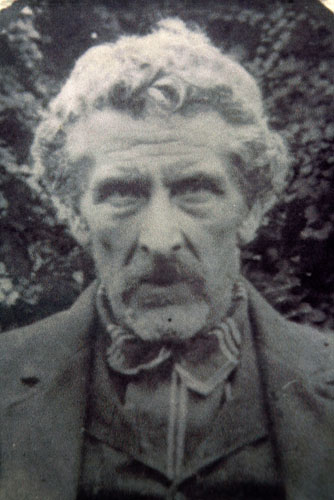

Photographs by Mike Cherin

When Mike Roselle tried to give his State Governor a sample of Mountain Top Removal dust for analysis, he was not expecting to be arrested at gunpoint and banged in jail for a week on suicide watch – all without charge.

A few seconds after he rang the doorbell, Roselle was surrounded by a dozen State Police officers, guns drawn.

A couple of weeks before Thanksgiving Mike Roselle decided he’d had enough.

Enough of the toxic dust in the air. Enough of the constant blasting that rattles his small house.

Enough of the poisoned well-water. Enough of the chopped mountains and buried streams. Enough of the forests, playgrounds and cemeteries plowed under for one more suppurating coal mine. Enough of seeing his friends sicken and die in the West Virginia county that has the highest mortality rate in the United States.

A straightforward mission

That November morning Roselle, the John Brown of the environmental movement, took a drive with his friend James McGuinnis up roads washboarded by the ceaseless transit of coal trucks to Kayford Mountain.

What used to be a mountain, anyway. Much of that ancient Appalachian hump has been stripped, blasted and gouged away by the barbarous mining method called Mountaintop Removal. Roselle’s mission was straightforward.

He aimed to collect some of the dust, the pulverized guts of the mountain, that showers down on the nearby towns and villages, streams and lakes, day after day, like deadly splinters from the sky.

Roselle scooped up a few pounds of that lethal dirt in a couple of Mason jars. He wanted to have the debris tested. He wanted to know what toxins it contained. Lead, probably. Arsenic, perhaps. Mercury? Who really knew. The mining companies weren’t saying. Neither was the EPA.

A dutiful servant – of Big Coal

Roselle got it into his head to take the mining dust to the one person in the state who might be able to give him some answers, to assure the folks who live under the desolated shadow of Kayford Mountain that there was no cause for alarm – the man who was charged with protecting the citizens of West Virginia from harm, the Solon of the Monongahela, Governor Earl Ray Tomblin.

On Thanksgiving morning, Roselle went to Charleston with his jar of dust. He walked right up to the Governor’s mansion and rang the doorbell.

Earl Ray is what you might call a lifelong politician. A Democrat, Tomblin was elected to the West Virginia senate fresh out of college in 1974. He was 22 at the time and has held elected office ever since. Across those four decades, Earl Ray has been a dutiful servant of Big Coal.

Every time a coal mine caved in, a waste dam breached, or an explosion of coal gases maimed and killed some miners, Tomblin would be there to offer his comfort. Consolation to the afflicted coal executives, that is.

Tomblin has raged against the ‘war on coal’. His administration has repeatedly sued the EPA on behalf of coal companies, citing its “ideologically driven, job-killing agenda”. And he has assured the mountain people of West Virginia that the coal dust fog that shrouds their communities is safe to breathe, eat or drink.

An unexpected turn of events

Then Mike Roselle showed up on Tomblin’s doorstep to make the governor prove it. Roselle didn’t expect to see Tomblin that morning, so he’d slipped a note inside the jar asking the governor to test the dust and report back to him on what it contained.

But a few seconds after he rang the doorbell, Roselle was surrounded by a dozen State Police officers, guns drawn. Roselle was immediately arrested, hustled into a waiting police car. He was not told why, apparently because the cops couldn’t find a section of the state code that Roselle had transgressed.

They drove him to jail anyway, saying simply they “had orders to bring him in.” Orders from whom, they didn’t say.

Over course of the next six days Roselle was kept jailed without charges, including three days inside the Hole, the disciplinary unit. Why? Because Roselle had refused food until they could inform him of the charges against him.

Later he was transferred again, this time into a glass-enclosure, the suicide watch room, where he was forced to wear an orange medical gown for two days. Then, suddenly, he was released on a mere signature bond.

Whose freedom?

A few weeks after Roselle walked out of that Charleston jail, a storage tank at a chemical ‘farm’ owned by Freedom Industries ruptured.

Out of a one-inch hole in a white stainless steel tank, a stream of a licorice-smelling crude began pouring onto the ground and into the nearby Elk River and downstream directly into American Water’s intake and distribution center – the primary drinking water source for the Charleston metropolitan area.

The chemical that contaminated Charleston’s water supply, forcing 300,000 to go without drinking water, was a compound called MCHM – 4-methylcyclohexylmethanol.

It’s used in the processing of coal and another highly toxic compound marketed under the name of Talon, which is manufactured by Georgia-Pacific, a company owned by the Koch Brothers.

Authorities not alerted

Freedom Industries discovered the leak early in the morning of January 9th, but never alerted state authorities or the water company. Hours passed before any attempt was made to stem the flow of the chemical into the Elk River. In that time, more than 125 people were sickened by drinking fouled water and sought treatment at area hospitals.

The fiancée of one of Freedom Industries’ top executives claimed that the illnesses were probably induced by the media. She said that she’d showered and brushed her teeth with the contaminated water and was “feeling just fine.”

As for Governor Tomblin, he took pains to reassure the people of West Virginia the spill that had fouled the Elk and Kanawa Rivers had absolutely nothing to do with the coal industry:

“This was not a coal company incident. This was a chemical company incident. As far as I know there was no coal company within miles.”

Selective unawareness

Apparently, Tomblin was unaware of the fact that nearly all of Freedom Industries’ contracts were with the state’s coal industry.

Nor that one of the company’s top executives, J. Clifford Forrest, is also the president of Rosebud Mining, a Pennsylvania coal mining company – which was recently sued for illegally giving advance warnings to mine managers of impending safety inspections by regulators.

On the afternoon of the Elk River spill, state legislators were meant to convene in the capitol building for a special session geared at passing a resolution denouncing the ‘war on coal’.

But the statehouse was evacuated before the great debate could take place, with lawmakers scrambling out the exits, coats over their heads, in a vain attempt to shield their lungs from the sickly-sweet smell of MCHM.

And to this day no one in West Virginia is quite sure whatever happened to Mike Roselle’s jar of dust.

Jeffrey St. Clair is the author of Been Brown So Long It Looked Like Green to Me: the Politics of Nature, Grand Theft Pentagon and Born Under a Bad Sky. His latest book is Hopeless: Barack Obama and the Politics of Illusion. He is on the board of the Fund for Wild Nature. He can be reached at: sitka@comcast.net.

This article was originally published on Counterpunch.

http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2311593/one_state_under_coal.html