Protecting the Cook Family Cemeteries

by Antrim Caskey

Bandytown, WV — Following a July 30 mountaintop meeting with Boone County Deputy Sheriff Randall White, members of the Cook and White families returned to their family cemeteries on Cook Mountain, Saturday, August 1, to mark off the 100-foot legally designated protective boundaries surrounding three historic Cook family cemeteries.

Boone County Deputy Sheriff Randall White confirmed with a family member by telephone on Saturday morning that the blue and pink ribbons marking the 100 foot protective boundaries around each of the three cemeteries had been fixed that same morning.

At each cemetery, family members measured the one hundred foot protective zone around each cemetery. Using orange ribbon, wooden stakes, and spray paint, the family marked the boundaries. Although difficult to discern at first, it appeared that Randall White’s men had been to Cook Mountain and made their own markings around the cemetery. The two sets coincided in general, however a few newly posted “no trespassing signs” were spotted within the protected boundaries. In addition, at the main Cook cemetery, holding almost thirty graves, the tape we found was at 50 feet from the cemetery.

Marvin White, Randall’s cousin, was still skeptical. “We have to keep an eye on this, keep a very close eye,” he warned.

Lindytown Access Road

Traveling the road up the Bandytown/ Lindytown/Twilight side of Cook Mountain proved to be quite a technical driving challenge, especially after days of heavy rain. The wash-out on this route, which according to the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WVDEP) is the official access route to the Cook family cemeteries, had been repaired, as Jeff Sammons, superintendent at the Horizon Resources job, told us on July 30.

However, the 4-wheel drive vehicle Billy Stewart drove us up in could not make the incline in the mud and we diverted our route to a spur off the main road to access the graves. “They need to fill that gully with gravel,” said Stewart. Indeed, it looked like the repair was temporary and well on its way to washing out again.

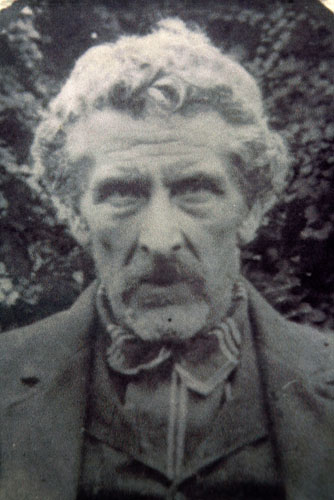

Standing at the largest of the three cemeteries, Leo Cook, 73, was born in December, 1935. He grew up on Cook Mountain. And he’s one of the few of his generation of Cooks who is still alive and living in the area. From the cemetery, Leo Cook pointed out where deep mining has occurred on Cook Mountain in the 1950s, “They had a drift mouth right over here and I watched them haul coal from under this mountain. They mined way down this ridge.”

Marvin White asked Leo Cook if he meant they mined underneath the cemetery. Leo Cook stood in the cemetery and shook his head, “I saw them take coal from right underneath us.”

In fact, the ridge where these cemeteries sit are ringed with highwalls. The last cemetery is just a couple of hundred feet from a perilous drop-off.

Crossing Roadblocks

Cook scampered up the pile of mud and rock debris and expressed disgust at the mine company’s actions, “they didn’t have to go and do this,” he grumbled as he topped the pile and looked back over his shoulder.

We walked along muddy puddled roads and climbed over four more of the man-made obstacles. We got muddier and muddier. At the second to last roadblock, where last week, volunteers from Rock Creek, WV shoveled a trough to drain a large lake of standing water, the roadblock had been re-established with additional mud and rock.

Ivan Stiefel, one of the July 30 volunteers, said when he heard that the mine companies had undone their work said, “I don’t know how a company can be so arrogant — to block a family from its heritage. Stiefel, an avid kayaker and a 2008 Brower Youth Award recipient, has been organizing around the issue of mountaintop removal for the past two years.

Mike Bowersox, a veteran activist with Seeds of Peace, who along with thirteen others also helped clear the roadblocks last Thursday said, “It’s an outrage that they’re denying the Cooks and the Whites access to their family cemeteries –that they’re blocking the route they’ve used for more than two hundred years.”

Family Stories

As we walked onward to Chap’s grave, Vickie Stewart held her grand-daughter’s hand. Jenna mentioned something about chips that were back in the truck, that she was getting hungry. Vickie told us how as kids she used to eat a lot of popcorn, “Growing up, we grew popcorn. We’d wait ’til it got hard and we’d rub and twist those cobs ’til our hands were covered in blisters. But we didn’t care, that’s how we got popcorn…I had an uncle that grew all different colors! Blue, pink, red….”

The trees stood thick and the temperature dropped as we walked the final path to Chap’s grave. Jenna turned and peeked at me over her shoulder, “I’ve had many friends that have had to move away,” she told me. “Like my friend Jordan.”

Jenna is ten and attends Van Elementary School in Van, WV.

I asked Jenna where did her friends live.

“Twilight,” she told me.

She got very quiet and her grandmother exclaimed,” Can you believe it, a ten year old has to deal with this, her friends moving away because of a coal company!”

What Coal Can Do To a Community: Twilight, West Virginia

Accessing the Cook cemeteries from Lindytown, you will drive through a tiny community called Twilight. Twilight is dying, on its last breath, you can almost see the blood flowing down the streets. “As soon as the grass gets three inches high, they’ll rob you,” said James Smith, who, with a heavy heart, just sold his home in Twilight and will leave the area.

“I just couldn’t live in a garbage dump…the main reason I sold is because there is no one left. I’ve got no one here and you can’t depend on strangers.”

Smith recalled a daytime looting he witnessed recently at a recently sold home across from him. “A pick up truck pulled up right along side that house and a bunch of men jumped out, loaded that vehicle up and drove right on by. They didn’t even look at me when they passed,” he told me.

Residents of James Creek are determined to prevent the same situation developing in their hollow and the blocked access to the cemeteries has sparked considerable worry and consternation.

“It’s like they want to erase us and pretend that we were never here,” said Maria Gunnoe, a community organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition. Gunnoe has worked extensively for years in the communities below Massey’s draglines — Twilight, Bandytown, Lindytown — are names that frequently bring tears to her eyes. Gunnoe was awarded the 2009 Goldman Environmental Prize for her work to stop mountaintop removal coal mining.

Defending Their Heritage

After measuring out the protective zone at Chap’s lone grave, Cook took us down the mountain on another road, to where his family home-place stood. Cook wanted to show us the old cellar and the well. The weeds had grown up so much that we could not locate them, but coming back up Cook found the old sleigh road they used to use. Cook led us up the hill, bushwhacking through the briars and mountain laurel, to the old drift-mouth where they took coal for use at home.

Sitting on the mossy bank, the mouth of the underground tunnel was opaque. Cook hopped inside and gave a yell. No one answered. He sat back down and folded his hands on his knee. Marvin Smith handed Jenna a shaving of a birch tree – she gleefully inhaled the minty aroma though she couldn’t understand how her grandmother used to chew it, as gum!

Cook told us that the mine company has threatened to prosecute him personally if they find him on their property. “I’ve walked off here hundreds and hundreds of times,” Cook told me. He gestured off into the woods, “right there used to stand an old apple tree — had apples this big around,” he said, cupping his hands hands generously as if holding a softball-sized fruit.

Twenty minutes later, at 12:15pm, as Marvin White walked one hundred feet into the woods with the measuring tape, Leo Cook held the other end, standing at the edge of the fence he put up around Chap’s grave two years ago.

We heard a deep blast rumble and pop in the distance. No one heard a warning blast.